Saving Monticello: The Newsletter

The latest about the book, author events, and more

Newsletter Editor - Marc Leepson

Volume XIX, Number 11 November

2022

“The study of the past is a constantly evolving,

never-ending journey of discovery.” – Eric Foner

THE MISTRESS OF MONTICELLO: “The greetings of South Carolina to the Master of Monticello—Floride Cunningham.”

Those words are inscribed to Jefferson Monroe Levy in a copy of the second edition of Miss Washington of Virginia: A Semi-Centennial Love Story, a privately published novel by Jeannie Blackburn, writing as “Mrs. F. Berger Moran.” Originally published in 1889, this edition of the short, melodramatic fictional account of the courtship of young Marie Washington, a grandniece of George Washington, came out in 1893.

Levy descendant Richard Lewis recently came across the volume among his late mother Harley Lewis’ books, and kindly sent images of the inscription. Miss Washington is a 19th century romance novel with a plot and ending that will surprise no one. Plus, it’s filled with cringe-worthy racist tropes whenever an enslaved person is mentioned.

That said, there is historical value in the book: the short but illuminating sketch of Jefferson Levy’s mother, Francis Mitchell (Fanny) Levy, which mentions, her role at Monticello during the first 13 years that her son owned the property. Jefferson Levy paid for the second printing; and Jeannie Blackburn wrote a short “In Memorium” about his mother, who had died in 1892 and was a fan of the book.

While researching Saving Monticello twenty-plus-years ago, I found a small amount of material that that shed light on the time Fanny Levy’s spent at Monticello, primarily letters that she wrote in 1881 to her sons Louis and Jefferson Levy and her son-in-law Marcus Ryttenburg in New York. They contained first-person accounts of the work Jefferson Levy did to repair, preserve, and restore the place after he bought out the other heirs of Uriah Levy in 1879, following a seventeen-year period in which the house and grounds had been all but neglected since his uncle’s death in 1862.

Monticello,

Fanny Levy wrote on July 4 1881, to her son Louis, “is looking elegant,” the “grounds

and scenery [are] magnificent.” Fanny Levy said, enjoyed a staff of “splendid

servants,” including "a good cook and waitress."Portrait of Fanny Levy

I also found references to one of the first large events held at Monticello, a fund-raising Colonial Ball Jefferson Levy put on to benefit the Albemarle County chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. A local newspaper reported that Fanny Levy “came down from New York to be [her bachelor son’s] hostess,” wearing “a colonial outfit of lavender in which she had her portrait painted later." The newspaper called the fundraising event “one of the most brilliant entertainments ever given in Albemarle County.”

What Jeannie Blackburn wrote in Miss Washington’s “In Memorium” adds to the picture of Fanny Levy’s time at Monticello. She “was widely known as the charming hostess of Monticello,” Blackburn wrote, “and will always be remembered as a lovely woman, cordial in her manner, giving genuine kind welcome to Monticello, taking great pleasure in showing the beauties of the old home to all her guests, and taking great care to have Monticello kept in the colonial style of the days of Jefferson.”

Fanny Levy “entertained many visitors at this grand old homestead, among them many prominent personages.” In 1889, Blackburn noted, “President Cleveland and some of his cabinet were guests.” Virginia, she said, “has lost a good friend in Fanny Mitchell Levy, Monticello a cherished mistress, and her children a mother who can never be replaced.”

As far as the inscription to Jefferson Levy is concerned, the woman who wrote it, Floride Cunningham of South Carolina, was the niece of Ann Pamela Cunningham, who founded the Ladies Association of Mount Vernon in 1856, which purchased George Washington's home—and owns and operates it to this day—from Washington’s nephew, who was about to sell the property to become residential housing lots.

Anne

Pamela Cunningham often is cited as the first American house preservationist—but

I’ve long contended that that honor should go to Uriah Levy, who did what she

did at Monticello twenty years earlier, in 1835.

JEFFERSON’S JEWISH GRANDCHILDREN: Yes, you read that correctly. I recently learned the

details in a revealing November 2020 essay, “The Jewish Grandchildren of Sally Hemings

and Thomas Jefferson,” by University of Virginia History Professor James Loeffler, who directs the

university’s Jewish Studies Program.

The story begins early in the early 19th century with the common law marriage of David Isaacs and Nancy West. Isaacs was a Jewish man who had emigrated from Germany and ran Charlottesville’s general store. West was a “free mixed-race woman,” Professor Loeffler writes, who “owned local property, ran a bakery, and launched one of the country’s first African-American newspapers.”

In 1822, the couple—who were raising seven

children—were hauled into court and indicted for the crime of “interracial miscegenation.” After

fighting the charges for five years, the couple prevailed.

In 1832, one of their daughters, Julia

Ann Isaacs, married Eston Hemings. He was the youngest son of Sally Hemings, a

mixed-race (her mother was biracial and her father was John Wayles, Thomas

Jefferson’s father-in-law) enslaved woman at Monticello.

DNA and historical evidence strongly

suggest that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Eston Hemings and his six

siblings. Eston Hemings, who was born in 1808, had been freed by Thomas

Jefferson in his will following his death on July 4, 1826.

They later moved to Madison, Wisconsin, where

they changed their last name to Jefferson. And, although Julia Ann’s father was

Jewish, the entire family “began to identify publicly as [Thomas] Jefferson’s

white, Christian descendants.”

You can read the entire essay at https://tinyurl.com/TJGrandchildren

Special thanks to my friend and Saving Monticello Newsletter subscriber Amoret Bruguiere for bringing Professor Loeffler’s essay to my attention.

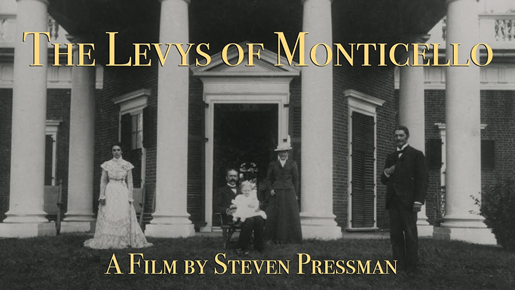

THE DOC: Steven Pressman’s great documentary, The Levys of Monticello, continues to

appear at film festivals. There’s an in-person

screening on Sunday, November 6, at the Virginia Film

Festival in Charlottesville, after which I’ll

be taking part in a Q&A with Steve, Susan Stein, Phyllis Leffler, and Niya

Bates.

For more info, go to https://bit.ly/LevyDoc

EVENTS: On Saturday afternoon, November 5, I will sign copies of Saving Monticello at the Monticello Gift Shop on the Mountaintop—the day before the Sunday, November 6 screening at the beautifully restored Paramount Theater on the Downtown Mall in Charlottesville.

If you’d

like to arrange an event for Saving

Monticello or for any of my other books, email me at marcleepson@gmail.com

For details on other upcoming events, check the Events page on my website: https://bit.ly/NewAppearances

GIFT IDEAS: For a personally autographed, brand-new paperback copy of Saving Monticello, please e-mail marcleepson@gmail.com I also have a few as-new, unopened hardcover

copies, along with a good selection of new copies of my other books: Flag: An American Biography; Desperate

Engagement; What So Proudly We Hailed; Flag:

An American Biography; and Ballad of

the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.